Introduction

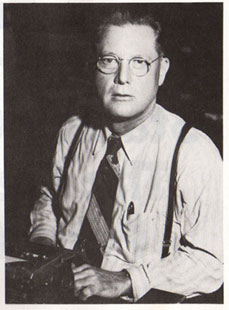

My approach to examining multimedia writing is that of the bricoleur 1, which takes me into various places in search of materials.This is how I found myself in the Harry Ransom Center, looking at an image of one of the most prolific writers in American history, Erle Stanley Gardner, who sat with a Dictaphone, sounding out some work of popular fiction. I had been looking for clues as to how writers wrote in multimedia prior to personal computers, and I was particularly interested in audio as part of the process. So it was the Dictaphone that first caught my eye. But the Dictaphone is just a piece of machinery. Something else about the image—something I could not identify—made me pause and return the next day for another look. Roland Barthes calls this something “the punctum.” It is that thing that “holds me, though I cannot say why.” It is the punctum and its “certain but unlocatable” effect that forces a pause. And the inability (momentary or prolonged) to talk about it, to name it, is important: “What I can name cannot really prick me,” Barthes writes. “The incapacity to name is a good symptom of disturbance.”2 I cannot name the punctum in the image of Erle Stanley Gardner, but I can describe the image. He is sitting, surrounded by all the artifacts of a predigital professional writer 3 . But one artifact is missing. He is surrounded by books, card catalogues, and filing cabinets, but he is not hunched over a typewriter. He is reclining in what appears to be a very comfortable chair, with a contemplative look on his face. He cradles the Dictaphone’s handpiece like someone who is holding a TV remote control and not quite committed to a particular show. He is relaxed, but at the ready. But what is he ready for? Perhaps the punctum, the thing we cannot name, is this: Is Gardner at work or is he just relaxing? The answer to this question determines, in part, the power we afford to writing as an activity, as distinct from the value of the literary product.4

By profession, Gardner was a lawyer. So was he writing as leisure, or writing for leisure? In the former sense, it is a diversion, a form of entertainment for the writer (and presumably for the consumer). But in the latter sense, writing is an investment for the writer.To explore this question further, we might look at another image of Gardner, this time at a typewriter. Both images seem posed, but in the earlier image at the typewriter, Gardner seems frozen in a more unnatural, uncomfortable position. He is looking straight at the camera, not at his text or even his fingers. The caption suggests that he is playing at work: “The creator at his typewriter. In most cases, Erle Stanley Gardner dictated his books and let his pool of secretaries do the finger work.”5 This is true of his novels, but as Dorothy B. Hughes points out in Erle Stanley Gardner: The Case of the Real Perry Mason, Gardner’s pulp fiction was “pounded out” on his typewriter after work. His early earnings clearly put his writing in the amateur realm. But by the time his first novel was published in 1933, he could have lived off his income from writing:

By profession, Gardner was a lawyer. So was he writing as leisure, or writing for leisure? In the former sense, it is a diversion, a form of entertainment for the writer (and presumably for the consumer). But in the latter sense, writing is an investment for the writer.To explore this question further, we might look at another image of Gardner, this time at a typewriter. Both images seem posed, but in the earlier image at the typewriter, Gardner seems frozen in a more unnatural, uncomfortable position. He is looking straight at the camera, not at his text or even his fingers. The caption suggests that he is playing at work: “The creator at his typewriter. In most cases, Erle Stanley Gardner dictated his books and let his pool of secretaries do the finger work.”5 This is true of his novels, but as Dorothy B. Hughes points out in Erle Stanley Gardner: The Case of the Real Perry Mason, Gardner’s pulp fiction was “pounded out” on his typewriter after work. His early earnings clearly put his writing in the amateur realm. But by the time his first novel was published in 1933, he could have lived off his income from writing:

In the first year of writing, 1921, he earned only $974, less than he made in a month as a lawyer. In his fifth year, his earnings had risen to $6,627. By the early thirties, his sales from writing had mounted to more than $20,000 yearly, a sizable income any day and particularly so in those depression times. At the pulp payment of a few cents a word, this meant a tremendous number of words pounded out on his typewriter night after night. He was prodigiously productive. The quota he set for himself was 1,200,000 words a year, or a 10,000-word novelette every three days, 365 days a year.6

And so we have two images of Gardner as a writer: one of a hack, pounding out a living in the pulp mags, and the other of an author/CEO, dictating to his secretaries. Gardner’s notes do little to privilege one image over another. Hughes explains his conflicting notes:

Gardner made a serious start at writing fiction in 1921. He has two differing versions and his two sets of autobiographical notes as to why he decided to try to write. In the 1959 version he explained that for virtually the first time in his life he had some leisure on his hands. He had long ago decided that unless a person was independently wealthy, only writers, who could take their work with them, or owners of mail order businesses requiring little individual attention could be completely independent. In the later 1969 version, he says that he had heard there was good money in writing, and why couldn’t he write?7

For Gardner, then, writing represented leisure, independence, freedom to travel, and capital. His mixed motivations read like the twentieth-century American dream, making a good living by living well. It is in the realization of that ideal that the cultural significance of his work becomes obvious. The works themselves maybe light, but the text he was writing was extensive, expansive, mutable, profitable, and powerful.

Although we may not be able to distinguish between work and leisure as it relates to Gardner, we can distinguish between the work and the text. In his essay, “From Work to Text” Roland Barthes differentiates the work from the text, suggesting that “the work can be held in the hand, the text is held in language, only exists in the movement of a discourse.”8 The text I am studying is not one that we can hold in our hands. In fact, each time we try to hold onto it, we’ll find that it slips out of our grasp. This slippage is common to all texts, but it is pronounced with Gardner’s text because of his volume, the collaborative nature of his process, and the multiple media streams involved in the creation and dissemination of his texts. Approaching the entire web of text created by Gardner is daunting. He wrote 82 full-length Perry Mason novels. And he had sold more than 300 million of those by the late 1970s.9 That is merely the figure for his best-known work. It leaves out much of his pulp fiction and his work under the pseudonyms A.A. Fair, Kyle Corning, Charles M. Green, Carleton Kendrake, Charles J. Kenny, Les Tillray, and Robert Parr.10 So volume undermines attempts to master Gardner’s work. Furthermore, we know that others are doing much of the work (i.e. typing) necessary to create the works (i.e. books, VHS tapes, DVDs,) that comprise Gardner’s huge oeuvre. For example, in addition to secretaries who did the actual typing, Gardner employed producers and television writers to adapt his works to TV.Every TV episode was a costly production of at least $100,000. 11 Gardner’s writing process began in collaboration and with multimedia in mind, with the text to be transcribed and disseminated as far and wide as it would go.

I began with a general question about what we might learn about multimedia writing by looking at Erle Stanley Gardner’s writing process. Just musing about this process leads to at least three practical questions: 1) How does one look at a multimedia process after it has ceased? 2) What manageable slice of the massive Gardner oeuvre should be represented? 3) How does one represent a slice of the process to an audience? The first question seems best answered by a close reading of various permutations of one chapter through multiple media alongside archival and biographical evidence. The second question would be best answered by a segment of the body of work that reflects Gardner’s own writing process through his characters. More specifically, the act of dictation appears in (at least) one of Gardner’s Perry Mason novels. It seems possible to glean some additional information about Gardner’s writing process by watching this particular scene develop across multiple media. Answering the third question surely requires a presentation environment that accommodates multimedia. To that end, multimedia versions of this scene are presented on this Web site where visitors will find audio of Gardner dictating this scene, excerpts from the manuscript, a reproduction of a popular version of the books, excerpts from the teleplay, a video clip from the TV show, more analysis of the texts, and technical notes about the production of the site.12 What follows will be a close reading of various multimedia permutations of chapter six of The Case of The Spurious Spinster, which in the original dictation and book includes a scene where Perry Mason uses dictation to coax information out of a taciturn fellow. I’ll trace the scene from the original audio dictation, through a manuscript taken from the dictation, to a popular copy of the book, a version of the teleplay, and a video of the TV show.