The weather, the news, disenchantment with the city, my penchant for Epicurean politics (i.e. retreat from them), and an apparently insatiable appetite for watching videos of people doing chores, off-grid, in cold environments, have all left me in a bit of a run-for-the-hills kind of mood. I daydream of just getting a plot of land in the mountains of Not Texas and just taking my family and whatever we can fit into (or strap onto) our cars and just seeing what life would be like if we lived intentionally on a homestead. This is a fantasy. We have kids in school, a suburban house, jobs that aren’t remote, student loans, etc. In my daydreams, we move into the wilderness by choice. In my nightmares, we move out of necessity because of some sort of disaster. In my reality, we just keep grinding. It’s possible that all this grinding will help bring about said disaster.

Sometimes I have to ask myself if grinding is really good for anything, anyone, or any environment. The longer we grind in the same place, the deeper the rut. That said, one can also get in the groove of a routine. Is a groove still the result of a grind or is it caused by something slightly more intentional? (Personally, I think you can tell the difference between a groove and a rut by the sonic atmosphere. But I’ll save that for another medium.) But what happens when things grind to a halt? COVID was rough in a lot of ways. Everything ground to a halt. Paired with some severe weather that our region was unprepared for, COVID forced me to think a lot about disasters, survival, technology, and ecosystems. In such systems, everything’s connected, but not everything reacts in the same way to the same event. While humans, as a species, got unhealthy during COVID, other parts of the ecology–like the atmosphere–improved. While the technology of photocopies did not proliferate during COVID, the QR code–which some assumed was a cute gimmick just a few years earlier–became ubiquitous. Shorebirds flocked back to their habitats when humans stopped gathering on the shore because of lockdowns. In the age of Anthropocene, we might just grind and cough ourselves out of existence, and/but this might make opportunities for other species to flourish in the post-Anthropocene. This is not the goal, mind you. This is depressing AF, especially when it’s been above 100 degrees for months on end, places as diverse as Canada and Hawaii had recent, catastrophic, deadly fires, Morocco recently had a deadly earthquake, and on and on and on.

In an effort to address the depression that comes with this situation, I’ve been experimenting with what I’ve come to think of as pockets of adaptation. Here are a few things I’ve been doing to keep myself from getting too depressed:

Culturing things. My backyard cultured dairy experiments have suggested to me that the strains of thermophilic lactobacillus do just fine in the heat. I’ve been making yogurt in jars mostly submerged in a water bath heated by the sun. I’ve tried to see what other things I could make by introducing different cultures into existing conditions in around my place. I strained the yogurt into labneh. I introduced the strained yogurt cultures into goat’s milk and strained that to make both labneh and goat cheese. I used a sour cream culture indoors because they are mesophilic and like the exact temperature that emerges when the air conditioner tries to keep up, but can’t.

Rejecting the stove and oven. I’ve discovered that both slow cookers and electric pressure cookers work great outside when paired with solar panels and a small inverter. Off-grid cooking is tricky in our current conditions. Wood and charcoal fires are out of the question due to burn bans. My current small solar inverters can’t handle many electric heating elements, microwaves, stoves, and the like, but they work great with slow cookers, suggesting that slow cooking and pressure cooking aren’t merely trendy. They are also efficient and portable which are important in these times of climate disasters.

Using the sun to preserve foods. I’m not a huge fan of sun-dried tomatoes or or raisin-like things, although I live in a good climate to try those things. But once it gets above 100 degrees, you can sun-dry almost anything. The original jerky was made this way. I’ve been able to preserve peppers, mushrooms, zucchini, and eggplant for more than a year by hanging them in the sun with a slight breeze.

Guerilla gardening. When water restrictions meant I couldn’t water my garden enough to keep the plants from shriveling and dying, I started looking for damp, partially shady spots along my normal grind path. I planted, sprouted, and kept alive a guerilla decorative gourd plant tucked into a municipal planter. I started thinking about gardening in the same way a trapper might set up a trap line. What if we cultivated the land along the grind paths that we cut through the earth? What if we cared for, watered, nourished, and collected vegetables on our way to work and back?

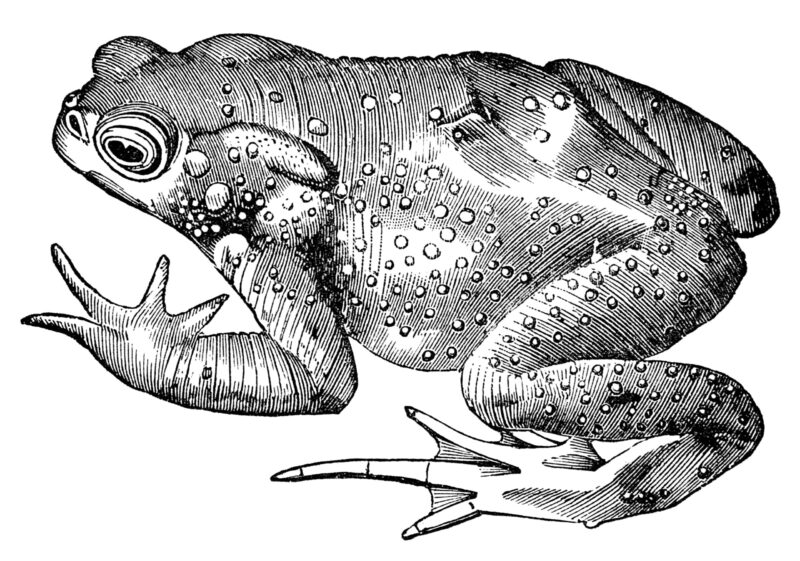

Creating accidental habitats. Given the lack of ability to garden like normal, I started thinking about how I might grow with hydroponics. When the soil temperature is too high, like it has been in most of my garden, things won’t grow, even if you water them. If they do happen to sprout, the sun with scorch them. By growing things in a water-based system, you can control lots of factors, including the temperature. I had heard rockwool was a good medium for growing in this way, and I had some scraps leftover from a studio-building project. (Rockwool is also a great sound insulator.) Reading that you had to soak the rockwool in water first, I filled up a box full of clean leftover peanut butter jars with water and a scrap of rockwool in each. I kind of abandoned the project for a while on my back porch. One day, when I went out there, there was a toad chilling almost totally camouflaged by the rockwool, which is the best toad-camo I’ve ever seen. It was unreal. If it hadn’t been for his eyes poking out above the water, I wouldn’t have seen him at all. Fearing he might be stuck, I adjusted the habitat so that he could easily escape. He stuck around for days. One day I saw him on a bucket lid. He would go out and eat and come back and chill. I’ve been trying, unsuccessfully, to build toad habitats for years using broken terra cotta pots and things. Then, one day, when I was trying to create something else, I accidentally created a toad hostel.

The through-line in these pockets of adaptation is that all of them required me to think differently about my environment. I had to tweak my habits and routines and what possibilities the intense heat offered or recommended. None of this, of course, will help the planet. I increasingly believe that only large-scale collective efforts coordinated among giant global players will help the planet. But those global players have to get their ideas from somewhere. Often they look to waves of social activism that emerge from the ground level and see where the action is. Thinking about how climate-related social activism might work made me remember a book I read many years ago. In Alternative Food Networks: Knowledge, Practice, and Politics David Goodman, Melanie DuPuis, and Michael Goodman write about how social food movements were evolving at the time (a little over 10 years ago): “This ‘new wave’ of social activism includes the burgeoning alternative food movement in its many and diverse forms, from local farmers’ markets to fair trade producer cooperatives.” The alternative food movements, as Goodman, DuPuis, and Goodman frame them, “offer a vision that people, by eating differently, can change the worlds of food as well.” But when they argue about changing the world, people who participate in food movements—and even people who analyze them—are often really arguing about changing capitalism. Goodman, DuPuis, and Goodman write that those kinds of economic changes are possible from within the framework of capitalism:

The new politics of food provisioning and global fair trade builds on imaginaries and material practices infused with different values and rationalities that challenge instrumental capitalist logics and mainstream worldviews. These alternative projects are seen as templates for the reconfiguration of capitalist society along more ecologically sustainable and socially progressive lines. The discursive and material development of such ‘spaces of possibility’ over the past 30 to 40 years demonstrates that alternative forms of social organization with their own operational rationalities can coexist, and even coevolve, with contemporary capitalist society.

“Spaces of possibility” is not a new idea or phrase. I think that’s why they put it in quotes over a decade ago. My “pockets of adaptation” isn’t a new idea either. It’s probably just a riff on spaces of possibility. But new isn’t always the important thing. Usually “new” is marketing and hype. Cultured dairy isn’t new. Sun drying foods isn’t new. Rockwool and Peanut Butter Jar toad habitats might be new, but that was an accident. Solar panels and electric pressure cookers are newer than toads and yogurt. Guerilla gardening is at least as old as Johnny Appleseed. These things–and the concepts behind them–can coexist, coevolve, and be co-opted by capitalist society, even as it grinds the anthropocene to an end. Maybe some network with nodes of adaptive pockets can stretch over the globe. Maybe AI will figure out climate change. Maybe these are just things to occupy our minds while the world burns. But I’m going to keep trying to accidentally make toad habitats.